The Spirit of Okinawa in Traditional Music

Okinawa Island’s subtropical location in the East China Sea is its greatest asset and greatest downfall.

Midway between mainland Japan and Taiwan, Korea and the Philippines, and just over four hundred miles off the coast of China, it made the perfect target for a U.S. military invasion near the end of World War II. In spring 1945, over 100,000 troops and 120,000 civilians were killed in the Battle of Okinawa. Homes, businesses, and centuries-old castles and other remnants of the former Ryukyu Kingdom were destroyed.

But even after this massive devastation, even after U.S. military occupation for the following twenty-seven years and continued military presence today, Okinawa has retained its unique culture that predates its transition to a prefecture of Japan. Its equidistant proximity to so many regions also made it a major trade destination, allowing Okinawans to pick up and meld together bits and pieces of traditions from across East and Southeast Asia.

This cultural amalgamation is heard in Okinawa’s folk music, which the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art presented last month with a concert by The Ryukyuans, the first in a performance series for the Music From Japan Festival 2014. The key instrument is the sanshin, a three-stringed snakeskin lute that came from China as the sanxian via Okinawa to mainland Japan where it evolved into the popular shamisen. The five-note musical scale bears resemblance to that of Indonesia; the wooden drums to those of the mainland and Korea. Lyrics are sung in the endangered languages of the Okinawan islands.

Together these elements create a sound that is uniquely Okinawan, a sound known in Japan as shima uta: island song. While a beautiful form of expression and entertainment, the music has also been a tool to rebuild and rejuvenate a once broken community.

“There is music flowing in our island all the time, because we love sanshin and music,” performer Isamu Shimoji said through a translator after the Freer concert. “We are proud of our traditional music and culture.”

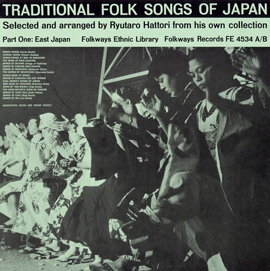

Hear a popular Okinawan folk song from the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings album Traditional Folk Songs of Japan:

While many Okinawans strive to preserve their heritage and native language through learning traditional folk songs, there is also a widespread effort to contemporize the music. In the second half of their set, The Ryukyuans performed a few of their original songs, incorporating an acoustic guitar alongside jazzy riffs on the sanshin and rock ’n’ roll rhythms on the shima-daiko drums.

“I want to convey the spirit of traditional music within my music,” Shimoji said, adding that he wants reach audiences beyond his homeland and the mainland. “Okinawan music has the potential to be embraced worldwide. That’s why we are expanding on the genre of Okinawan music.”

The Ryukyuans are helping to create a new amalgamation that reflects an American presence, Western influence, and this growing global community.

Elisa Hough is the editor for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She spent three months in Okinawa, where her mom was raised as a military brat, researching the links between the island’s traditional and contemporary music and documenting her findings in a blog, oki yo!

Erina Takeda, a development intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, conducted the interview in Japanese.