Atomic Nancy: Sounds of Los Angeles

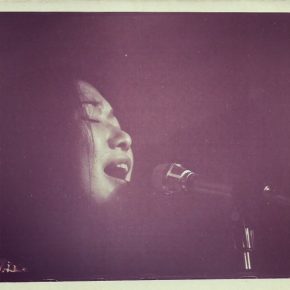

Nancy Sekizawa has a voice like a knife. Her piercing alto rings so sharp and clear you can almost see it. She brings this force to all her musical practices—whether singing at the Buddhist Temple during obon or for the Sunday services at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles.

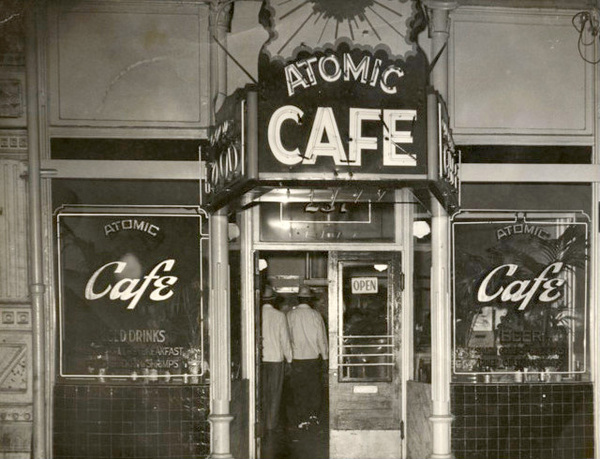

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Sekizawa is known as Atomic Nancy. The moniker refers to the restaurant her parents opened in Los Angeles in 1946, Atomic Café, but it also describes her powerful personality. She has strong opinions and she speaks her mind, a quality she likely got from her parents, Ito and Minoru Matoba.

When they first opened their restaurant, Japanese Americans were returning to California after their World War II removal and exclusion from the West Coast. Many were cautious about the way they referenced Japan or Japanese culture in their public behavior. Unfazed, Min Matoba named their joint to commemorate the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Sekizawa worked in the Atomic Café as a kid, making the daily journey from West L.A. and later Hollywood to Little Tokyo, a historical Japanese American neighborhood in downtown L.A.

When she was a teenager, she was drawn as much to the psychedelic music of the 1960s as she was to the Japanese popular music that she heard around the house and from the restaurant jukebox. She sang choir in high school and was an early member of the seminal Asian American jazz band Hiroshima. In the 1970s, she presided over the family’s restaurant and transformed it into a late-night landmark in Los Angeles’s nascent punk scene. Later, after seeing the toll of drug and alcohol addiction on the musicians in her community, she became a certified drug counselor, work she has done now for thirty years.

Atomic Nancy draws energy and inspiration from music. Here’s how she describes the sonic experiences formative to her sense of identity and well-being.

What was the music you heard as a kid?

I had a phonograph when I was three years old. I would play all the kid records. And my dad would bring home the records from the restaurant’s jukebox that were no longer popular. And he would just give it to me like it was like my pacifier. My favorite song was “Pancho López,” which I played over and over.

I remember how my dad would end a night of work at the restaurant by playing five or six songs from the jukebox that he really liked—because for twelve hours he had endured all the other trash on the jukebox. And on Sundays on the way home in the car, my parents would tune into the Japanese radio broadcasts. Japanese language and music were around us all the time. So I grew up loving enka and minyo, old Hawaiian Japanese music, too. Yeah, this is the stuff I keep in my heart.

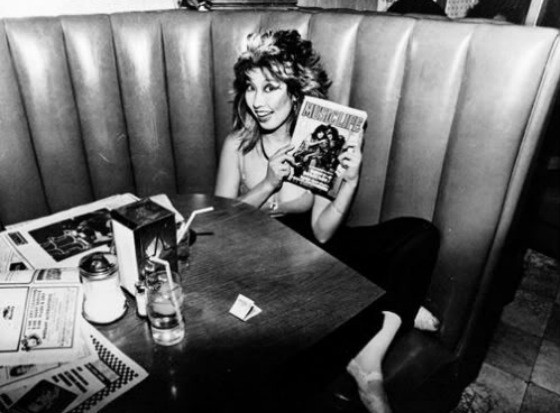

When did the Atomic Café transform into a punk rock hang out?

Around 1977, 1978. I started doing it slowly. I was listening to the Rodney on the Roq radio show, and there was a whole different element of music coming in at this time. These were like three-minute or thirty-second songs on cocaine. It was great! I would listen to these when I was cooking in the kitchen. And then I would see punk groups coming in—and they thought the place was cool, and they started bringing folks in.

So I went to a local record store, Vinyl Fetish, with some young kids, and we bought a bunch of records that I stuck in the jukebox to see how they would do. It was not mainstream stuff—it was punk bands of the time—local bands like the Bags, Plugz, X, Darby Crash. And bands would bring their own records, too: “Hey, we just cut a record, can we put this in your jukebox?” So the word got out that we were doing this, and after that, I was getting records from everywhere—from Europe, New York—shipped to me. I started sticking them in the jukebox, and that’s how it started.

Where do the local Japanese American and Asian American music scenes fit into your life?

I was a freshman in high school, and I was working late hours at the Atomic Café—like ’til four in the morning. These guys would come in every other night—they looked really different from all the other Japanese Americans. They would hog up a whole table, and they would order a lot of food and just eat and hang out for hours until after we closed.

They told me they were in a band—these were the guys who would become Hiroshima later. I was playing keyboards, and they were looking for a keyboard player, so they told me to come to one of their jam sessions. I did, and I sucked! But I said, “I can sing, too!” And when I sang, it turned out great. “You’re in!”

I was in high school, so I didn’t drive. They would pick me up to go to rehearsals in Long Beach. But first we’d have to go by Cal State Long Beach, where Dan Kuramoto from the group was teaching Asian American studies. He was one of the first people to introduce classes on Asian American history at college. I found the classes really interesting. I liked the activism of it.

As far as the music we were playing—it was experimental, acid rock. It was more rock ’n’ roll. We did covers—Santana, “Evil Ways.” We were listening to Pink Floyd, Dr. John. When June Kuramoto came into the group with her koto, she brought in the pentatonic scale, a more Asian sound. But then after I started my own family, I dropped out of the band.

For over forty years now, I have participated in programs of Nobuko Miyamoto and her arts organization Great Leap. Rehearsals have been at the Senshin Buddhist Temple for forty-five years. I love Nobuko and the temple’s former minister, Reverend Mas Kodani—they have so much heart.

I have also played in the temple’s taiko group, Kinnara. I felt like I was an angry Asian woman—so I just wanted to pound all this energy into something. I also was involved with another group there that plays gagaku, seventh century Japanese court music. It’s really difficult. It’s organic. There’s no counting. It’s like a drone.

And since the late 1990s, you’ve also been singing regularly in an African American gospel choir, yes?

About seventeen years ago, I hit an emotional bottom. It was after my husband died and a badly failed relationship. I was feeling pretty f*cked up and needed some spiritual help.

I had heard the First African Methodist Episcopal choir before. So I went to the church one evening. I sat in the back in the dark. When they started rehearsing, it was so powerful. They were singing from their hearts. They sounded so pure. So beautiful. It made me cry in my seat.

Someone came over to me from the choir and asked, “Hey, what brings you here?” I’m not religious, but I said, “Maybe it’s God?” She said, “Oh, hallejuah!” She asked, “Do you sing? Do you know what part you would like to sing?” There was no audition—it was all just spirit. She grabbed me by the hand, walked me up to the group, and said, “This is Nancy. She’s joining us.” They all clapped, and I haven’t left since.

What holds all this together—what is it about all of these different musical scenes that speak to you?

Here in L.A., we’re in a city of minority populations. And we’re okay with that. We’re trying to develop a sense of unity among communities and ethnicities. It’s so cool that I can mix myself into all of this. I don’t want to go anywhere else.

I’m really spiritual, but I don’t have a foundation in a single religion. I don’t know anything. I couldn’t quote you anything from the Bible. I just feel it. I listen to certain things, certain music, because I hear spirit in what’s good and what’s not. I hear solutions to challenges. It’s a feeling. If it moves me, then I do it.

Music has always given me inspiration, even in my darkest times. I used to sit in front of the jukebox at the Atomic Café. I would sit there and put in quarters—just giving me inspiration. When I walked into the AME church, I was sold. It was all about gratitude. You realize that you’re “above ground.” You’re alive. So you have to do something for someone today. Or at least try. I have been trying to do that in my job as a counselor for over thirty years now. And I sing three services each month. They are very heavy, very powerful, very high energy. I feel like I did a marathon each time I leave there. It’s awesome.

So that’s what it’s like, that’s what happened. Oh, man! It’s like that gospel song says—I really like this one—it says, I got a reason, I got a reason to praise the Lord!

See Atomic Nancy perform along with FandangObon at the Folklife Festival in the Sounds of California program. The group is in Washington, D.C., through July 4, and then the Festival continues July 7 to 10.

Sojin Kim is a co-curator of the Sounds of California program at the 2016 Folklife Festival.